APS TOGETHER

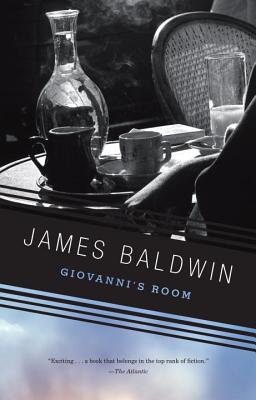

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

Hosted by Carl Phillips

Began on September 16, 2020

Share this book club

Giovanni's Room is a fever dream of language, desire, tenderness, those brief moments in which we think we know ourselves and others, the larger moments when we realize the quest to know anything for sure may be unresolvable—yet we keep questing, anyway. It's a meditation, too, on otherness—in terms of class, sex, race, and of intimacy maybe most of all.

Daily Reading

Day 1

Part 1, Ch. 1, pg. 3-13 (up to "to be the son of such a mother")

September 17, 2020 by Carl Phillips

The opening paragraph is a perfect example of Baldwin’s gift for compression, his ability to say a great deal in a brief space, and also to suggest something about the trajectory of the novel’s sensibility itself. The first three sentences are dominated by the I. The next two sentences attach the I to an image: a reflection, an arrow, blond hair, a face. All of these then get replaced by the speaker’s ancestors. So there’s already transformation going on, and I’d say this book is very much about transformation – how we transform those whom we encounter, and how they transform us, for better AND worse….Sticking with this paragraph, notice the analogy: speaker is to arrow as speaker’s ancestors are to conquest – conquest as an arrow of destruction across Europe, then the sea, until arriving at the Americas. Baldwin’s specification that the speaker is blond puts this into particular, racial context. All of this, while someone has a drink and looks out the window!

Day 2

Part 1, Ch. 1, pg. 13-27 (from "Years later, when I had become a man" to “if monkeys did not—so grotesquely—resemble human beings.”)

September 18, 2020 by Carl Phillips

One of the things I love about Baldwin, but especially in Giovanni’s Room and Another Country, is his ability to get at how much who we are is conundrum – he makes it almost palpable. It’s something he has in common with the Greek tragedians. Every Greek tragedy occurs at the intersection of what society expects of an individual and what that individual in fact desires; there can be no resolution without terrible sacrifice, which is not resolution, just an outcome…Back to Baldwin. Intimacy and distance. David – our narrator, who now has a name – wants distance from his father, but what he gets is his father’s intimacy forced upon him, and it makes loving his father impossible – because being intimate allows him to see his father for what he is. Meanwhile, David fled from the intimacy he had with Joey, and it has made it impossible for him to love himself; but the more distance he puts between himself and Joey, the more he craves/is tormented by the intimacy they enjoyed.

Day 3

Part 1, finish Ch. 1 & all of Ch. 2, p. 27-43 (from "This bar was practically in my quartier" to "the light of that gloomy tunnel trapped around his head.")

September 19, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Our first encounter with Giovanni himself. Notice the two figurations that Baldwin uses to describe him: first it’s as if Giovanni “were a promontory and we were the sea;” two paragraphs later, he is described as a boy for sale, standing with “arrogance on an auction block.” Nothing is random in Baldwin’s work, in this novel especially. Baldwin knows full well that the auction block conjures the idea of slavery. And the earlier image suggests that Giovanni is an object to be used, a place from which to launch oneself into a sea that has itself been described one of sexual murkiness (iniquity?). With these two images, we see Giovanni as pure tool with which to get a job done. More exactly, we see that this is how David – being the speaker – sees Giovanni.

Day 4

Part 1, Ch. 3, p. 44-61 (up to “to reach out and comfort him”)

September 20, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Day 5

Finish Ch. 3 (end of Part 1), p. 61-71 (from "Our oysters came and we began to eat" to "so many desperate and drunken mornings.")

September 21, 2020 by Carl Phillips

It’s a curious moment, when David decides that the people he’s surrounded by – the patrons of the restaurant, Giovanni, Parisians in general – are “people I would never understand.” And his impulse is to go “home,” as if that could prevent him from succumbing to “shameful” behavior. Yet he knows that his situation is nothing new for him. It’s a kind of spiritual lost-ness, akin to Augustine (in the Confessions) finding himself in “the region of unlikeness,” where he recognizes simultaneously what he believes he should do and his equal desire/inability to do it. It’s one of the few moments where, almost, I feel sorry for David.

Day 6

Part 2, all of Ch. 1, p. 75-84

September 22, 2020 by Carl Phillips

The opening of part two lays out a fascinating physics/metaphysics: joy and amazement, at their peak, seem to bring about their own demise, getting displaced by anguish and fear – across the surface of which David and Giovanni lose “balance, dignity, and pride.” Another way of putting it is that too much happiness makes them remember that their happiness is societally forbidden, which leads to fear, which in turn leads to shame about the behavior that led to their happiness. Argh, indeed!

Day 7

Part 2, all of Ch. 2, p. 85-102

September 23, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Another arrow! This time, it’s the light bulb dangling from the ceiling of Giovanni’s room. First, it’s described as being like “a diseased and undefinable sex in its [the room’s] center.” Then it’s a “blunted arrow.” It’s hard for me not to put the two images together and see a penis. And it’s this, according to David, that illuminates not just Giovanni’s room but Giovanni’s soul. Whether or not that’s true, that’s how David sees it, and it says a lot about his sexual confusion and about his repulsion when it comes to his own frankly human desires…And it’s interesting what kind of logic this brings out in David: destruction is apparently the way to achieve freedom: “I was to destroy this room and give Giovanni a new and better life.” But to give himself a new and better life, he has to become part of the room himself, the very room that he has to destroy for Giovanni’s sake…This strikes me as the circuitous logic of the desperate and deeply haunted.

Day 8

Part 2, all of Ch. 3, p. 103-118

September 24, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Earlier, I spoke of how rooms here tend to be claustrophobic, the sites of murky activity, sexual and otherwise – the bar, the restaurant, Gionvanni’s room, Joey’s room long ago. With chapter 3 of part Two, the murkiness is outdoors, and David describes it almost like a scene from Dante’s Inferno: “Nevertheless, beneath me – along the river bank, beneath the bridges, in the shadow of the walls, I could almost hear the collective, shivering sigh – were lovers and ruins, sleeping, embracing, coupling, drinking…” Meanwhile David generalizes interior spaces as the antidote to these wraith-like lovers, he imagines “Behind the walls of the houses I passed” that husbands and wives are putting their children to bed, having ordinary (i.e., not sexual) concerns, making for their families a “web of safety.” An interesting shift, also troubling how easily David forgets his own home life, the same way that, when he says he needs a woman and children “to become myself again,” he forgets who and what he is. Or can’t remember. Or doesn’t want to. Or has never known himself.

Day 9

Part 2, Ch. 4, p. 119-136 (up to “'We’d better get some sleep.'”)

September 25, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Chapter 3 ends with Giovanni telling David to hug him: “Viens m’embrasser.” Chapter 4 opens with the arrival of Hella, who says to David, when he just stands there, “t’embrasse pas ta femme?”: “You aren’t going to hug your woman?” (Or maybe “You don’t hug your woman?” I don’t know French, really.) So, a parallel is established. So, when David tells us that when he does hug Hella he felt “that my arms were home,” it’s not that credible. His resistance to hugging Giovanni has to do with his having determined that he needs to leave Giovanni, he feels trapped by neediness. Holding to the analogy, then, even if he does hug Hella, represents a similar trap. She’s decided she wants David. But across the novel, David panics and runs from whoever needs him.

Day 10

Part 2, finish Ch. 4, p. 136-148 (from "I got to Giovanni's room very late" to "the sash of his dressing gown.")

September 26, 2020 by Carl Phillips

When Baldwin wrote this book – and when I read it – the general thinking was binary: you were a man or a woman, you were gay or straight. It was radical when Baldwin spoke almost matter-of-factly about bisexuality in Another Country. In Giovanni’s Room, that subject doesn’t come up specifically, but now we learn that not only did Giovanni marry a woman and have a child with her, but he was happy (including sexually) in that life. He didn’t leave because of ‘discovering’ his sexuality, but because of grief and a suddenly-broken faith in God. It seems that his first sex with a man is out of necessity – he needs money, clothes, a job – and then it becomes, what, habit? Does that mean Giovanni isn’t gay?

Day 11

Part 2, Ch. 5, p. 149-157 (up to “and the shadow of death.”)

September 27, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Astonishing how automatically citizens will cling to xenophobia – and in this case, homophobia –when something goes wrong, nationally. It’s always not only easier to attack difference, but to be relieved by confirmation that one’s own people would never succumb to things like murder and sexual ‘waywardness.’ “It was fortunate, therefore, that Giovanni was a foreigner,” says David – the fact reinforces national pride, i.e., national prejudice. Look at the relief people still seem to have in this country when the latest act of terrorism turns out to have been done by a foreigner – and how quickly, when that’s not the case, the public assumes mental illness (another prejudice) or they struggle to explain how the perpetrator somehow had a troubled childhood…

Day 12

Part 2, finish Ch. 5, p. 157-169 (from "By the time we found this great house" to The End.)

September 28, 2020 by Carl Phillips

Way back on 9/24, I quoted David saying “But the end of innocence is the end of guilt.” David has clearly lost any innocence before he ever came to Paris. As he becomes more estranged from Hella, though, he says: “My guilt, when I looked into her closing face, was more than I could bear.” Is this a contradiction, then? Or, given that he can still feel guilty about the situation with Hella, is there some part of it that remains innocent? I begin to think that his naïve thinking about Hella’s ability to somehow save him might be a form of innocence…