APS TOGETHER

Day 2

Part 1, Ch. 1, pg. 13-27 (from "Years later, when I had become a man" to “if monkeys did not—so grotesquely—resemble human beings.”)

September 18, 2020 by Carl Phillips

One of the things I love about Baldwin, but especially in Giovanni’s Room and Another Country, is his ability to get at how much who we are is conundrum – he makes it almost palpable. It’s something he has in common with the Greek tragedians. Every Greek tragedy occurs at the intersection of what society expects of an individual and what that individual in fact desires; there can be no resolution without terrible sacrifice, which is not resolution, just an outcome…Back to Baldwin. Intimacy and distance. David – our narrator, who now has a name – wants distance from his father, but what he gets is his father’s intimacy forced upon him, and it makes loving his father impossible – because being intimate allows him to see his father for what he is. Meanwhile, David fled from the intimacy he had with Joey, and it has made it impossible for him to love himself; but the more distance he puts between himself and Joey, the more he craves/is tormented by the intimacy they enjoyed.

What does it mean, if we can only love a person according to how little we really know them – is it like this for all children, when it comes to loving their parents? And what if we can only love ourselves if we refuse to look too closely at what we are? Baldwin knows that love is basically impossible, and that it is equally impossible for us to resist trying to find it.

And yet, I can’t really say that David doesn’t look closely at what he is, at least once the accident occurs. His father’s vulnerability in the wake of the accident seems to have a clarifying effect on David – or maybe it’s more accurate to say it has a solidifying effect, since from that point on, David distances himself by creating a convincing persona, enough to make the father feel better about himself.

As for clarifying: It’s also important to remember that when David assesses himself at the end of chapter one, he’s doing so from the vantage of many years later, in the wake of something we haven’t yet learned about. NOW he can explain to himself the episode with Joey, NOW he can say a thing like “I succeeded very well – by not looking at the universe, by not looking at myself, by remaining, in effect, in constant motion.” But the David who is catalyst for everything that will now follow in the novel still lacks this self-knowledge, and thinks he will “find” himself by going to France, even as he also knows now that he knew then “at the very bottom of my heart, exactly what I was doing when I went to France.” More conundrum!

David suggests that this idea of going somewhere to find oneself is especially American. Is it?

Fascinating how time is handled in this novel. Time, and story. By p. 23 we have yet to meet Giovanni, but we know he will be killed by guillotine. On that same page, we are introduced to Jacques, but no sooner than he’s been described – but David hasn’t yet met up with him – we are thrown forward in time to a conversation David and Jacques have on the morning of Giovanni’s being sentenced. So, chapter two begins with David about to go meet Jacques for dinner, then we get the conversation that comes much after that, then we return to the evening of David and Jacques having dinner for the first time. Time interrupting itself. Or time being just as all-over-the-place as the narrator, both in physical space and in terms of morality.

It doesn’t take long to realize that what David means by le milieu is what, at the time, must have been considered the world of sexual ‘deviance’ – so-called ‘loose’ women, men like the boy who works at the post office and comes out “at night wearing makeup and earrings and with his heavy blond hair piled high,” men referred to as les folles (the movie La Cage aux Folles comes to mind) who refer to each other as “she.” He may have crossed the ocean, but he has sought out the very thing he claims to be fleeing, even if by this time he is involved with Hella. By his own analogy, he’s a hypocrite: he claims to be disgusted with le milieu but in the way that people hate to see monkeys eating their own excrement, because they see themselves in the monkeys. David sees himself in le milieu, and hates it, and can’t stay away.

Baldwin says there are two choices, either we remember our individual innocence – our Garden of Eden, as he puts it – or we forget it, and we engage, accordingly, either with “madness through pain” or “madness of the denial of pain.” I can’t decide which type of madness is David’s madness. There goes the restless arrow on that moral compass again…

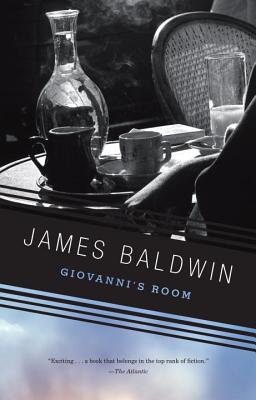

Personal note: I first read Giovanni’s Room in my 20s, before I had come out, when I was so much in apparent denial of my own queerness that I truly didn’t recognize it. That would take me ten more years. Reading this novel didn’t help matters. The depiction of le melieu, the character of Jacques (who seemed a stereotypical old “queen,” bitter, unloved, paying people to keep him company), and the inner turmoil of David’s character – I rejected all of it as having nothing to do with who I was. Also – like David – I couldn’t look away. I lived in a small town that bore no resemblance to the Paris of Baldwin’s novel. The book was an escape from that, into something that also made me relieved to realize, each time I put the book down, that it was ‘just’ a book, that my life was an entirely different thing. Thank goodness we sometimes outlast our own delusions.