APS TOGETHER

Day 10

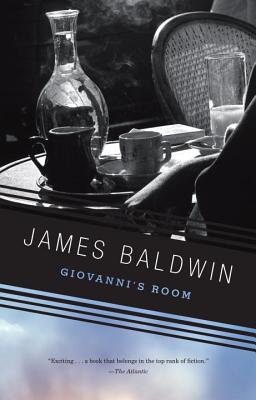

Part 2, finish Ch. 4, p. 136-148 (from "I got to Giovanni's room very late" to "the sash of his dressing gown.")

September 26, 2020 by Carl Phillips

When Baldwin wrote this book – and when I read it – the general thinking was binary: you were a man or a woman, you were gay or straight. It was radical when Baldwin spoke almost matter-of-factly about bisexuality in Another Country. In Giovanni’s Room, that subject doesn’t come up specifically, but now we learn that not only did Giovanni marry a woman and have a child with her, but he was happy (including sexually) in that life. He didn’t leave because of ‘discovering’ his sexuality, but because of grief and a suddenly-broken faith in God. It seems that his first sex with a man is out of necessity – he needs money, clothes, a job – and then it becomes, what, habit? Does that mean Giovanni isn’t gay?

An important distinction in the book, and for Giovanni and David, is between the act of sex with a body and sex as a felt commitment to a person. As Giovanni says to David: “You are the one who keeps talking about what I want. But I have only been talking about who I want.” That distinction is what allows David and Giovanni to speak of Jacques, Guillaume, and their hangers-on as a “disgusting band of fairies.” They see themselves as something nobler, cleaner. A huge part of Giovanni’s despair is that David was the first person who made him believe that what he had thought was dirty and sinful could in fact be beautiful. In being abandoned, he has nothing left to rescue him from what he sees as hell. Heaven and hell – as if those were the choices. Binaries, again.

“But I’m a man,” I cried, “a man! What do you think can happen between us?” – David says to Giovanni. This moment hits home each time I read it, having grown up with no models for intimacy between men, at home or in the media. When the only examples available are frightening and/or considered ‘degenerate,’ it’s easy to believe, absolutely, that you can’t be queer – you don’t recognize yourself in what you see, therefore you aren’t that. The power of societal assumptions and expectations can be crushing. David only knows one definition for being a man; likewise, Hella is boxed in by what she’s been told being a woman means. Surprisingly, only Giovanni can imagine possibilities past what society has always handed down as the ‘right way.’

This book follows the seasons. The relationship between David and Giovanni begins late winter, blossoms in spring, and now that – as David says to the policeman – “the autumn is beginning,” the relationship is dying. It’s interesting that David’s impulse is not just to leave Paris but to go south, where it will be warmer. In the same way that David moves from location to location, in a search for home, he seems to think that something like innocence or wholesomeness or psychological stability is attached to warm weather. (Hella, though, has spent the whole time in warm weather and found herself constantly adrift.) As we know from the opening of this novel, the south of France eventually gets very cold and David has been abandoned by Hella. Should they have moved to the tropics?