APS TOGETHER

Day 8

Moment. Pages 321-352.

August 13, 2020 by Ilya Kaminsky

How interesting to compare these lines from “The Three Oddest Words” to her other negations, to see how her perspectives develop. Say, compare it to “The Railroad Station” or to the ending of “Frozen Motion.”

“When I pronounce the word Nothing,

I make something no nonbeing can hold.”

Her capitalization of “Nothing” reminds me of my favorite literary anecdote: A German poet, Hölderlin, right before they put him in a mad house, was running around the apartment, possessed as if after a visitation from the divine, shouting:

“Nothing! Nothing is happening to me!”

The word “nothing” appears quite a lot in Szymborska. For instance, “Nothingness unseamed itself for me too” alludes to Heidegger’s well known essay, “What is Metaphysics?”

Curiously, when an interviewer asked Szymborska about the influence of existentialist philosophy on her worldview, she responded: “existentialists are monumentally and monotonously serious; they don’t like to joke.”

Speaking of Nothing: it is rather hard not to mention here another famous WS:

“Why, then the world and all that’s in’t is nothing;

The covering sky is nothing; Bohemia nothing;

My wife is nothing; nor nothing have these nothings,

If this be nothing.”

And what happened to our conversation about Szymborska’s love poetry? There is a lovely piece, “A Memory.” To be honest, I am not sure if it can be considered a love poem. Not at all. And, yet, I want it to be. It is many things…

We were chatting

and suddenly stopped short.

A lovely girl stepped onto the terrace,

so lovely,

too lovely

for us to enjoy our trip.

Basia shot her husband a stricken look.

Krystyna took Zbyszek’s hand

reflexively.

I thought: I’ll call you,

tell you, don’t come just yet,

they’re predicting rain for days.

Only Agnieszka, a widow,

met the lovely girl with a smile.

…a note of compassion, a recollection, a playful scene, a glance. But emotion is here, and is unmistakable; a poem of jealousy, fear, pain, ends up with a bit of wonder, yes? The speaker looks back through the years, the poem ends up with a smile.

I love how often playfulness is paired with metaphysics in Szymborska’s work. Take, for instance, “A Few Words on the Soul”: “We have a soul at times. / No one’s got it nonstop, / for keeps.”

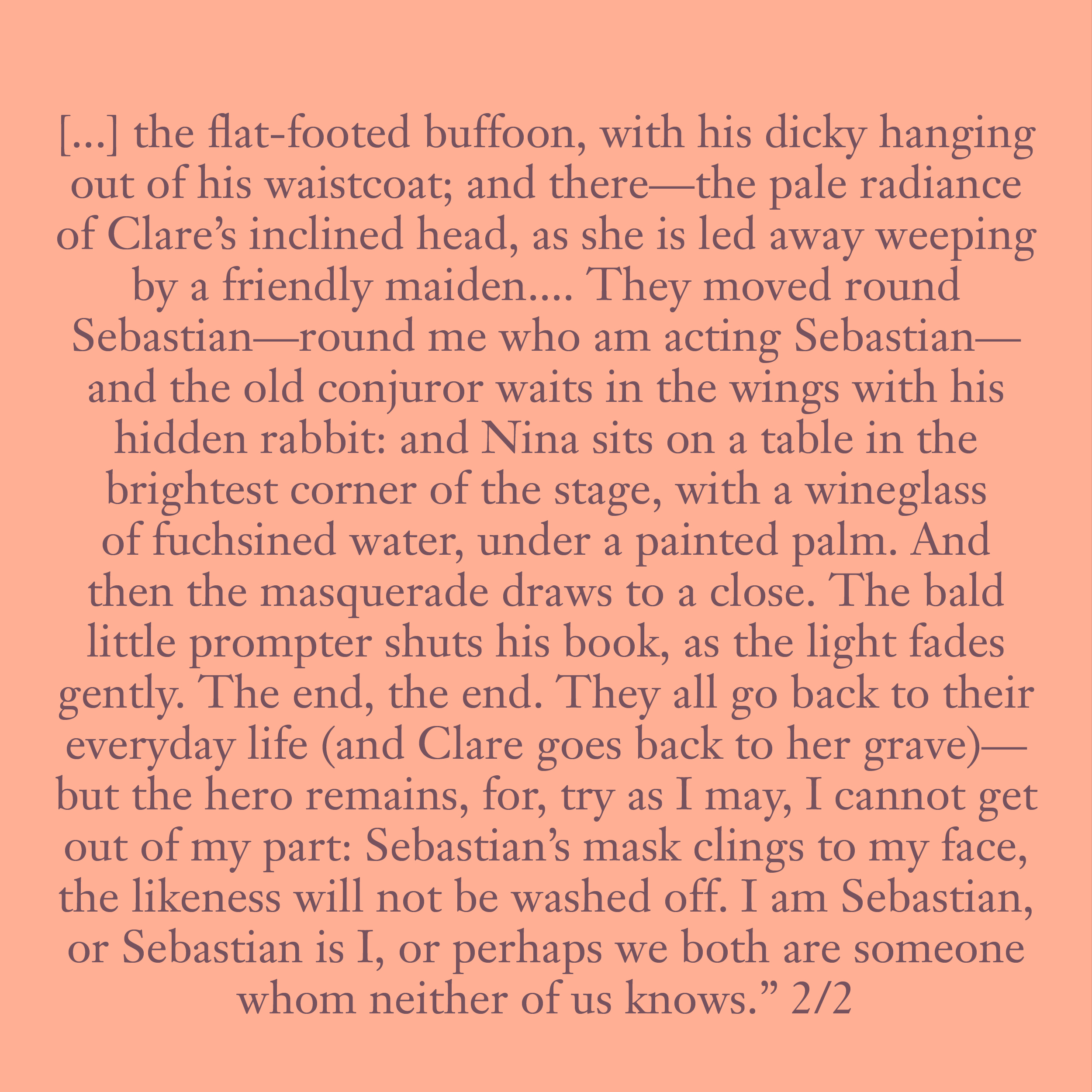

Have you read Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight? It’s the first novel Nabokov wrote directly in English.

Check out the last paragraph on pages 121 and 122. You will be astounded by what he says and how it relates to Szymborska’s statement in “A Few Words on the Soul.” I don’t put it lightly. You will be astounded. I know I was.

There is so much wonder at our “unknowing” in her work. I mentioned this earlier. But here it is, again: that unknowing, the soul:

It won’t say where it comes from

or when I’s taking off again,

though it’s clearly expecting such questions.

We need it

but apparently

it needs us

for some reason too.

Here is a collection of random objects from Szymborska’s flat, now collected in one of Krakow’s museums:

I tell my students to beware of generalizations. But like any practicing poet, I know all too well that there are exceptions to any rule. Which is why I find Szymborska’s “A Contribution to Statistics” (p. 341) such a delight. Here are a few lines from that poem:

“Out of a hundred people

those who always know better

—fifty-two,

doubting every step

—nearly all the rest,

glad to lend a hand

if it doesn’t take too long

—as high as forty-nine […]”

But soon the light irony of her use of bureaucratic lingo, of trying to explain what cannot be explained, gives way to emotion:

“hunched in pain,

no flashlight in the dark

—eighty-three

sooner or later…”

This “contribution” to statistics intrigues me. Yes, I admire the way it brings together humor and blunt statement. But there is more: by the end, the poem becomes almost a kind of wisdom literature. To be honest, when it comes to “wisdom literature” I consider myself a skeptic. But the use of specifics here, all the percentages, all the numbers, does keep my attention for a moment, and then it comes: the emotional punch in the gut:

“mortal

—a hundred out of a hundred.

Thus far this figure still remains unchanged.”

Is it a surprise that the most interesting, most durable poem about 9/11 was written by a Polish poet. You can find it on p. 344:

They jumped from the burning floors—

one, two, a few more,

higher, lower.

The photograph halted them in life,

and now keeps them

above the earth toward the earth.

Each is still complete,

with a particular face

and blood well hidden.

There’s enough time

for hair to come loose,

for keys and coins

to fall from pockets.

They’re still within the air’s reach,

within the compass of places

that have just now opened.

I can do only two things for them—

describe this flight

and not add a last line.

I marvel at “Photograph from September 11”—so many of Szymborska’s characteristic themes and poetic devices are included in this piece. So much of this (use of detail, treatment of time, perspective, etc.) have already been covered in our conversation about her work. And, yet, how fresh it still feels: how emotional these details become for this poet’s American readers, how much is said in the final line’s negation, their final refusal to “add a last line”! It’s as if Cassandra from the early poem is here again: she is looking directly at Americans, telling us what she sees.