APS TOGETHER

Day 1

Calling Out to Yeti. Pages 19-55

August 6, 2020 by Ilya Kaminsky

Let’s begin our conversation with “Classifieds,” the poem on page 32. Why so late into the book? As per the translator’s own afterword:

“It took her three volumes… to become the poet Wisława Szymborska, or so her own editing suggests.”

As we begin, ask yourself: how much of this book is authored by Szymborska, and how much by her translators Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Barańczak? And, yet: note how little credit (in very tiny letters on the cover!) the publishers give them.

Fun fact: “We have translated virtually all of the poems… with exception of a very few that Szymborska herself conceded were untranslatable. You’re lucky, she said about 1 of them, you only wasted 3 weeks on it. It took the Dutch translator 6 months to give up.”

More fun facts: Her collected works number some 350 poems. Asked why she had not published more, she answered, “I have a trash can at home.”

"Classifieds"

Szymborska’s poems always happen in the midst of life. So it is fitting for us to begin with “Classifieds.”

From the start, we see that this is a poet of tonal variation: from miraculous to humorous to mundane to philosophical to compassionate.

What drives this variation? Vocabulary: we are given “Sinanthropus’s jaws,” and “old folks’ homes.”

More on variation/juxtaposition: note how easily abstraction of the first three lines coexists with the list of random details in the last five lines of this stanza.

I TEACH silence

in all languages

through intensive examination of:

the starry sky,

the Sinanthropus’s jaws,

a grasshopper’s hop,

an infant’s fingernails,

plankton,

a snowflake.

As always in Szymborska: ideas go hand in hand with emotion:

WHOEVER’s found out what location

compassion (heart’s imagination)

can be contacted at these days

is herewith urged to name the place,

and sing

As always in Szymborska: no matter how light-touch the piece might be, the reality lurks very close at hand. How chilling to read this in the time of COVID-19 pandemic, knowing what has just happened in America’s own nursing homes.

“WANTED: someone to mourn

the elderly who die

alone in old folks’ homes.

Applicants, don’t send forms

or birth certificates.

All papers will be torn”

As always in Szymborska: there is playfulness, and a little bit of pain. But even pain seems to coexist with the delight of her light touch.

“FOR PROMISES made by my spouse,

who’s tricked so many with his sweet

colors and fragrances and sounds—

dogs barking, guitars in the street—

into believing that they still

might conquer loneliness and fright,

I cannot be responsible.

Mr. Day’s widow, Mrs. Night.”

A question for the reader: Think about the form of this poem. Could you write a piece in a similar form yourself? See how Szymborska does something similar again in “Advertisement.”

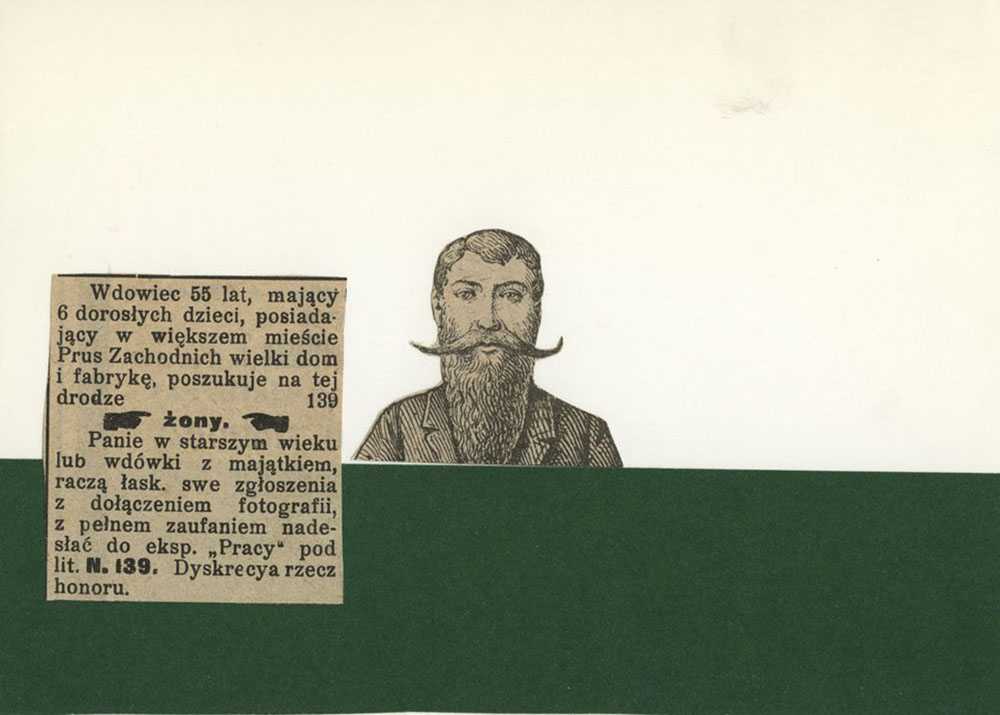

In the 1960s, Szymborska began to make collages that she sent, in the form of postcards, to a circle of friends. This collage makes me think of her “Classifieds.”

Something to consider: as we go forward, see how this poet develops over the years. See what she chooses to retain, note how certain strains from this piece’s texture will appear many years later in her work, in pieces such as “The Three Oddest Words.”

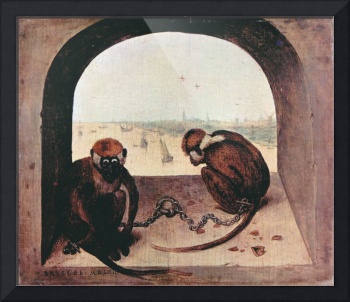

"Brueghel’s Two Monkeys"

Note tonal variations: This is a nightmare poem (“This is what I see in my dreams about final exams”) and yet there is always a comic element at play (“the sea is taking its bath”).

Note the juxtapositions: of large (“the exam is History of Mankind”) and local (an awkward “I” in “I stammer and hedge”).

The nightmare continues, as does the mocking (“One monkey stares and listens with mocking disdain”) and yet there is so much tenderness: (“when it’s clear I don’t know what to say / he prompts me with a gentle / clinking of his chain”).

And, yet, this compassion is twofold, isn’t it? Much to say about this duality: the speaker is being examined, but it’s the monkey that’s in chains.

The poem was written many decades ago, yet I can’t help but think about our very own moment of environmental crisis. So many dualities: the humanity is, as ever, self-centered and failing to examine its failings. It is nature that examines us, and yet it is nature that’s in chains.

I love that final “clinking,” at the end: so much feeling in the sound a chain makes via an image in this line.

Magnus J. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire note: While “Two Monkeys” refers to the painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (1562), “it is more specifically relevant to Poland: written in 1957, it was widely interpreted as a condemnation of the repressive atmosphere of the recent Stalinist period. Coincidentally, many scholars throughout the ages have seen this painting as a protest against political repression (notably the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands).”

"Notes from a Nonexistent Himalayan Expedition"

The title of Szymborska’s first famous book, Calling Out to Yeti (published in 1957), is drawn from this poem. To my mind, much of this poet’s metaphysical worldview can also be traced here.

In fact, Calling Out to Yeti is not Szymborska’s first book. But it is the book that has established her as an original, inimitable voice. It is the book that gave her poetry a new perspective on things. What kind of perspective? The poet speaks about human species/condition, as if trying to explain it to someone who knows nothing about it, as if explaining it for the very first time ever: how strange we are.

This awe, marvel, humor, this bewilderment at our strangeness is something that will continue in Szymborska’s work for decades.

First of all, who is Yeti?

A creature in Himalayan folklore, Yeti later came to be referred to as Abominable Snowman in western popular culture.

Szymborska is calling out to Yeti over and over via the repetitious structure of this piece: the content and form work hand in hand.

While at it, Szymborska juxtaposes various wildly different bits and pieces of our strangeness, both lighthearted and tragic:

“Yeti, down there we’ve got Wednesday,” the poet addresses.

“We’ve inherited hope—

the gift of forgetting.

You’ll see how we give

birth among the ruins.”

By the end: it is about the strangeness of our being on this planet.

By the end: it is about the strangeness of our need to speak “inside four walls of avalanche,” stomping our feet.

By the end: this piece is an ars poetica: it describes Szymborska’s perspective on the world as well as her view of what poetry itself is doing.