APS TOGETHER

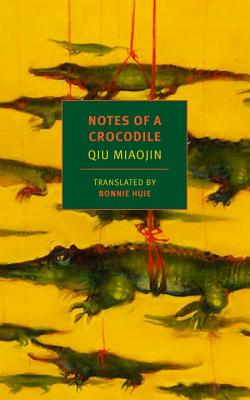

Notes of a Crocodile by Qiu Miaojin

Hosted by Paul Lisicky

Began on June 17, 2021

Share this book club

What did it feel like to be queer and alive in 1990s Taipei? How to be a college student adrift on a surf of lust and frustration? Qiu Miaojin aims to capture those questions and more in this mashup of letters, aphorisms, and meditations on a reptile, a vehicle for a country’s fixation on taxonomy at a time of newness, after thirty years of martial law. Satiric, irreverent, frank, poignant, exasperating, self-destructive, tender—part diary, part novel, part experimental film.

Paul Lisicky

is the author of six books including Later: My Life at the Edge of the World, an NPR Best Book of 2020; The Narrow Door, a New York Times Editors’ Choice and a finalist for the Randy Shilts Award; as well as Unbuilt Projects, The Burning House, Famous Builder, and Lawnboy. He directs the MFA Program at Rutgers University-Camden, where he is an associate professor and the editor of Story Quarterly. He lives in Brooklyn and Provincetown.

Qiu Miaojin

(1969–1995)—one of Taiwan’s most innovative literary modernists, and the country’s most renowned lesbian writer—was born in Chuanghua County in western Taiwan. She graduated with a degree in psychology from National Taiwan University and pursued graduate studies in clinical psychology at the University of Paris VIII. Her first published story, “Prisoner,” received the Central Daily News Short Story Prize, and her novella Lonely Crowds won the United Literature Association Award. While in Paris, she directed a thirty-minute film called Ghost Carnival, and not long after this, at the age of twenty-six, she committed suicide. The posthumous publications of her novels Last Words from Montmartre and Notes of a Crocodile made her into one of the most revered countercultural icons in Chinese letters. After her death, she was awarded the China Times Honorary Prize for Literature.

Daily Reading

Day 1

Pages 5-34 (through "That's the kind of song Meng Sheng wrote for me.")

July 8, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

The crocodile, a major figure in the book, makes an early appearance without much in the way of context. Is it some figment of interiority? A figure for queerness? An actual talking animal? Miaojin enjoys keeping the reader destabilized. As we read about the power outage and other mishaps, we might be thinking these are metaphors for starting a novel. Then: “That’s how it is, writing a serious literary work.” The narrator lets us know she’s in on the joke, quick to laugh at herself.

Day 2 | pp. 37-58 (through "If that many people secretly liked them, that’d be totally embarrassing.")

July 9, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

“I’m the same as you,” says Shui Ling to the narrator, and we suspect this is as close to acknowledging queerness as they’re going to get. How does the imperative to be indirect (or secretive) complicate their attachment? Does it drive them apart?

Day 3 | pp. 59-82 (through “Why, my dear crocodile, how are you?”)

July 10, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

The stunning coldness of the breakup! The narrator: “I was just writing you the letter in which I dump you.” Shui Ling dishes it back after a recovery: “That won’t be necessary.” & the allusion to a story in which murder is foreseen but can’t be stopped.

Day 4 | pp. 83-105 (through “Take a cue from the media, and show them where you draw the line.”)

July 11, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

The indelible portrait of Tingzhou Road attic, not just the space (“a narrow slit of a room”) but Lazi’s roommate, who gives the impression of someone who’d borrow money and never pay her back. Estrangement, aloneness—they’re enacted in every word.

Day 5 | pp. 106-129 (through “This woman had to be part of some hellish eternal recurrence.”)

July 12, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

What to make of Meng Sheng calling upon Lazi to witness Chu Kuang’s moment of anguish? That howl appears to require an audience member so that they can be “attuned to a common frequency.” Though the grief is real, Lazi watches as if it’s theater.

Day 6 | pp. 130-153 (through “I’ve never met another crocodile before.”)

July 13, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

In the letter to Shui Ling, it’s startling to hear “you and my family were the only ones who loved me” when this family is rarely on the page. Is that the unspoken story, the one too hard to tell? Their inability to welcome a queer daughter/sibling?

Day 7 | pp. 154-177 (through “I wanted to go home. Home….”)

July 14, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

For Lazi, lust is a barrier, a complicator. It gets in the way of her longing “to be close to someone.” She decides that platonic love is the way out of her “prison,” so she vows to be more affectionate and real with Tun Tun and Zhi Rou.

Day 8 | pp. 181-204 (through “And because it wasn’t love.”)

July 15, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

Meng Sheng, “freewheeling lunatic,” distracts Lazi from despair after the second breakup with Shui Ling, but his role is complex. While he saves Lazi from self-destruction, he pushes her toward “total depravity.” Is their making love a part of that?

Day 9 | pp. 205-225 (through “There was tenderness in her eyes.”)

July 16, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

Fascination with the other morphs into a need to control. Mioajin captures that idea so acutely and darkly with National Crocodile Month, “an opportunity” for crocodiles to register with government agencies.

Day 10 | pp. 226-242 (through to the end)

July 17, 2021 by Paul Lisicky

The collision of Xiao Fan's illness, her boyfriend's betrayal, her boyfriend's firearms accident, her clueless request of Lazi to check up on him. No wonder Lazi needs to detach and extract herself from the "jaws of suffering" to the point of cruelty.